- Home

- Emily Rubin

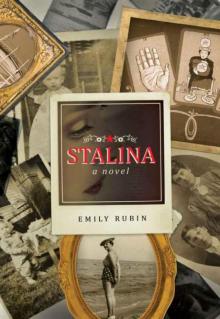

Stalina

Stalina Read online

Stalina

Emily Rubin

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Stalina Folskaya’s homeland is little more than a bankrupt country of broken dreams. She flees St. Petersburg in search of a better life in America, leaving behind her elderly mother and the grief of the past. However, Stalina quickly realizes that her pursuit of happiness will be a hard road. A trained chemist in Russia, but disillusioned by her prospects in the US, she becomes a maid at The Liberty, a “short-stay” motel on the outskirts of Hartford. Able to envision beauty and profit even here, Stalina convinces her boss to let her transform the motel into a fantasy destination. Business skyrockets and puts the American dream within Stalina’s sights. A smart, fearless woman like Stalina can go far… if only she can reconcile the ghosts of her past. Obsessed with avenging her family while also longing for a new life, Stalina is a remarkable immigrant’s tale about a woman whose imagination—and force of personality—will let her stop at nothing.

Emily Rubin

STALINA

A Novel

For Anne

“Just as the future ripens in the past,

so the past smolders in the future.”

Anna Akhmatova

Prologue: Birthday

I was eighteen years old on the third of March, 1953. My mother allowed me to invite three friends to celebrate in our tiny Leningrad apartment.

“Why only three?” I complained.

“There are no parties permitted while Stalin is so ill. If three come, it’s not officially a party, but you still must be very quiet.”

My mother often turned the truth on its side to explain things she did not want to talk about. Stalin lay on his deathbed for days, and all of Soviet Russia listened to radio reports of his failing health around the clock. My mother feared any backlash if jocularity was heard from our apartment during so solemn a time.

“How many people make a party?” I asked and showed her the design I wanted to make for the top of my cake. I had drawn a big, broad apple tree filled with fruit.

“Four,” she said, “not including the host, because then you have two couples who can play cards while the host serves tea. No more about that. What will you use to decorate your birthday cake?”

My mother’s answer about four making a party was made up, just like the story about my father fighting the fascists. By that time he was already dead, starved to death in a prison I never knew to visit. “Sour cherry drops for the apples, spearmint gums for the leaves, and chocolate sticks for the branches and body,” I explained.

My mother told me I was clever.

The “not-a-party” birthday was on a Monday after school. I carefully chose my guests—Amalia, who always wore a worn-out red velvet ribbon in her hair; Alma, who had one crossed eye; and Olga, whose mother let her cut her own hair. I served layer cake with icing made from plums and fruit compote. To keep the party a secret from our neighbors, we agreed to be like the silent film stars Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, and Rudolph Valentino—responding to anything, happy or sad, with our faces and bodies, no sound allowed. It was great fun, and my mother could keep her uninterrupted vigil at the crackling radio without worrying about a visit from the black uniforms and leather boots of the police. Two days later Stalin died without waking. My mother, who named me after him, was never the same. That was a long time ago. Everything is very different now.

Chapter One: Reds

To begin my story, I offer this blunt self-portrait, the real Stalina Folskaya. My nose is long and pointy and slightly skewed to the right. My arms are thick and well muscled with just a bit of softness on the underside. Gravity of the flesh comes with age, as I have recently reached my sixty-seventh year. I still have a strong back and shapely, wide hips. Most pleasing to me are the long, slender fingers of my hands. I keep my nails carefully manicured and painted a deep red called “Heart Stopper” from Revlon. My grandmother Lana used to pick at the skin around her thumbnails, and I do the same. I have her hands exactly, even down to the ridges on my right thumbnail. Yet, it is hard to believe I am now, in 2002, almost the same age she was when she died. How can that be? In Russia, years before I came to the USA and the Liberty Motel, a palm reader once told me the indentations on the nail represent a deeply buried pain that has not yet surfaced, but will someday. I paid her only two rubles for the five-ruble reading because she could not tell me more about this “pain.” I left the last three rubles clutched in my unread palm.

I said to her, “I have experienced much heartache because of stupid, selfish people. That is pain enough.”

She yelled after me, “Don’t be stingy with your future, Stalina. Pay the three rubles, and I’ll tell you about the pain! You will be much better off.”

“I like not knowing,” I responded.

That was a very difficult time. It was 1991, and the Soviet Union was finished. My world was bankrupt. I had much to think about. It was then I started to color my hair. Brunette was my true color, but I find black more dramatic for my pale skin. In Russia I used a dye made in Cuba called “Zarzamora,” which means blackberry bush. My friend Olga, who grew up to run her own hair salon, would get the hair dye along with boxes of Cohiba cigars from a comrade in Havana. She used the cigars for bribes on the black market when her salon was running low on hair spray and nail polish. Here I use L’Oreal’s “Blackest Black,” a less deep but longer-lasting color. From the back, my head looks like a bush filled with shiny black crows. The abundance of hair makes me appear larger than my five-foot frame. With my rugged Russian looks, I choose never to go into public without makeup. My dark brown eyes are always lined with black kohl and my eyelids a little covered with a creamy blue eye shadow called “Sky Blue” from Coty. I like to call the eye shadow “Leningrad Blue” because it reminds me of the sky above the Neva River back home, when the long days of summer sunlight make the blue sky pale, soft, and forgiving. My lipstick is a dark blood red called “Can-Can” from Revlon. I read in Russian Woman magazine that red lipstick gives lips a full, attractive, sexy appearance and communicates a well-developed ego.

I dress comfortably in black stretch leggings and blouses of washable silk. I wear a lab coat at work over my clothes. As an employee of the Liberty Motel, my old lab coat is very useful. There will be more about my workplace later, but now I will tell you about leaving my mother and my country.

Chapter Two: Good-bye

It was late September in 1991 when I said good-bye to my mother, Sophia, at her rooming house for the elderly on Lermontovsky Prospekt. At seventy-nine, she was too old and too stubborn to leave Leningrad.

“Fine, stay,” I always replied.

My mother’s room in the defunct school had high ceilings, a cement floor, and six metal-framed cots set against faded pink plaster walls. Smells of rusting metal and boiled cabbage filled the air and made it heavy, but nourishing to our complexions. The last time I was there, we were alone, but even so we spoke in whispers simply out of habit.

“I don’t like your hair that color,” she said.

“The black?” I replied as I positioned a photograph of my father above the headboard of her sagging cot. “Shall I hang the picture of Father here?”

“You look like a whore,” she added.

I had taken that picture of Father outside our dacha near Lake Ladoga, north of Leningrad, shortly before he was arrested in 1952. He was gardening in the blue coveralls he wore for his job at the loading docks at the shipyards on the Neva. He took that job after the school where he taught literature fired him for assigning The Scarlet Letter to his students. The headmaster disapproved of Hawthorne’s provincial attitude. My father thought it told things in a very human way and tried to defend his course of teaching. It could have been any book—they just wanted to get rid of him. It was

a bad time to be a writer and a Jew. The job at the docks was grueling. He would come to the dacha on the weekends very tired, but would go to work in the garden as soon as he arrived. My mother would have a bush or tree she wanted planted, and she would promise to make his favorite mushroom blinis if he dug holes for a rhododendron or two. He was saddened about not teaching, and I once saw him late at night from my window burying his books in the holes. He thought it would protect them—this time from the censors. During wartime our city buried many monuments and works of art to protect them from the bombs.

Father read to me in English. It was his favorite language. A good balance for our harsh Russian minds, he would say. Every night until I was thirteen he filled my head with Shakespeare, Steinbeck, and Dickens. Big books, every word, one at a time. He laughed at the attitudes of French and Italian, and was uncomfortable with the wild tempo of Spanish. I am not partial, but from him I learned my English very well. Then he was gone.

But back to my mother. “I think it looks dramatic,” I said, referring to my hair color as I hammered a nail into the wall with the heel of my shoe.

The photograph was the only decoration in the room. I sat on the cot next to my mother and stroked her arms up and down gently, tickling the hairs along her raised blue veins. She slowly rocked back and forth. Her crippled hands, which had once kneaded mounds of flour and water into sourdough bread, felt dry and brittle, like kindling that could be snapped.

“What’s that smell? You ate garlic?” she said, sniffing in my direction.

She hated garlic, and I’d had garlic soup for lunch.

“Father looks handsome in that picture, don’t you think?”

“Police eat garrr-lic…I itch.”

“Where?” I asked.

“My ass has sores from the sandpaper they use for sheets.”

“Petroleum jelly?” I had packed some with her things.

“You’re a hussy who fucks the police!”

“Moth—” I stopped myself.

No point to protest.

She continued, “Don’t touch me, you reeking whore!”

I had grown accustomed to Mother’s ill-tempered dementia. The five other women who shared her room also ignored her rants. A bare light bulb dangling from the ceiling cast shadows of the six cots and divided the room into long, dark corridors. A burning coal stove left a darkened halo of soot on the pink plaster ceiling. I was sweating, and my mother had difficulty breathing. The roommates were at the commissary having tea and cake. Mother waited till they finished because she preferred not to talk to them and liked the tea at its darkest, from the bottom of the samovar.

“I need it strong for my digestion,” she would say.

“Would you like me to walk you downstairs?” I asked.

“And then are you also going to wipe my ass?”

“No, Mother. Good-bye, Mother.”

I kissed her forehead and left her sitting at the very edge of the cot, her stockinged feet barely touching the floor. The starch in her flowered dress helped her to sit up straight, and the dampened heat of the room made her white hair into a frizzy, glowing halo. She looked like a mad angel awaiting a task from the Almighty.

She yelled after me, “I’ll be dead soon, Stalina. Remember, you ate cake while Stalin lay dying!”

Leaving her room, I looked through the hallway windows at the clouds hanging high above our newly renamed St. Petersburg. I imagined my angel mother soaring with wings spread wide, shouting her words down to earth like a trumpet: “Come near me and I’ll show you my ravaged ass, then I’ll take a nip of yours and spit it down your throat! I’m going to cripple you to your toes with nausea, that way you cannot leave me.”

Walking down the hallway, I could hear her rugged smoker’s cough followed by a wet gurgling sound from deep within her lungs.

I thought, “She’s my mother and I know it’s wrong, but I won’t miss cleaning up her raving angel ooze.”

It was a long, noisy walk down the marble corridor to the nurse’s station. The nurse on duty grabbed my bribe of a box of twelve brassieres right out of my hand. They would sell or trade easily in post-Soviet Leningrad, and I wanted my mother to have special attention. I was given three boxes of brassieres and a carton of toilet tissue as salary from my last month of work at the laboratory where I had come up through the ranks and become an “engineer of aroma.” Before I was given this honorable position, I had spent many months cleaning test tubes. It was important work as well. No residue was safe from my strong action and technique. I was well schooled from my chemistry degree, and it soon became clear to my supervisor that I had done much more than just memorize every element on the periodic table.

The work of the lab was to manufacture scents, but not perfumes. Our tinctures were used when something needed to smell like what it was not. It was fascinating but strange work. For example, agents from the KGB would come to us when they needed to smell like residents from places where they were on assignment. You may not know someone from Leningrad has a different odor than someone from the Balkans or Siberia. Foreign lands as well were in our beakers and crucibles. Armenia, China, or France. We studied the eating, dressing, and lovemaking to give the agents the perfect cover, so no sniffing police dogs would discover their identity. Later on our work became top secret when the KGB needed to have a place to store dangerous chemicals and vaccines, products of military domination. The Soviet Army had their weapons, and we were to disguise them with the sweetest of aromas. Blackberry, amber, rose, and more.

Anyway, I saved some of the bras to sell in America, and the toilet tissue I left with my mother. The nurse slipped the bras under her desk and gave me an unenthusiastic nod with raised eyebrows.

“Have a pleasant journey,” she mumbled.

I walked out onto Lermontovsky Prospekt, making my way toward Nevsky, where capitalism had haphazardly taken hold. Hundreds of billboards above the buildings along the main thoroughfare broke up the sky like an unfinished jigsaw puzzle. Blocking my view of St. Isaac’s Cathedral was a giant woman’s hand holding a freshly brewed cup of steaming black coffee.

* * *

I remember when our city was Leningrad—before it was once again St. Petersburg, as in the time of the czars—banners of our leaders decorated the same buildings. Walking to school one day, when I was about twelve, I stopped to watch as four workers hung an enormous poster of Stalin that filled the entire side of a building near the Fontanka Canal. Prominent in the foreground was our venerable leader, Secretary General Stalin, immaculately groomed, proud in his uniform, and behind him a hydroelectric plant. His salt-and-pepper hair was brushed back off his high forehead. Thick, lustrous eyebrows accentuated that smooth and unshakable brow. His almond-shaped hazel eyes gazed in a direction slightly to the painting’s left, but more prominently out, to the future he saw for us. His perfectly tailored gray wool uniform was decorated with gold epaulets on the shoulders, red stripes on each side of the collar, and a gold star hanging from a crimson ribbon bar, pinned just above his left chest pocket that had a buttonless, double-stitched curved flap. It is a tricky piece of tailoring, if you’ve ever tried to sew.

I felt so much pride watching the poster unfurl down the side of the building; I was breathing heavily, my eyes liquid with emotion. Now that I thought of it, that image of Stalin must have brought up my first romantic feelings toward a man. My heart beat strongly under my heavy knit sweater, and through clogged nostrils I took sharp breaths as the tears streamed down my cheeks. I could not pull myself away. I wanted to live his vision. His hands proudly held a proclamation declaring the Soviet Union’s economic and scientific superiority. All I wanted was for those hands to caress my face and for those arms to hold me next to him. I imagined myself in the poster, with his arm around my shoulder as we both looked out on the future, with the rushing water of the hydroelectric plant behind us, the power of Mother Russia clear in her generous natural resources, brilliant leadership, and worshipful youth.

&n

bsp; There was a humility in Stalin’s image that added to my infatuation. Behind him a red flag unfurled and framed his broad shoulders, and across the top of the poster the words of Lenin were inscribed on a field of red: “Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the entire country.” Stalin was doing all the work, but he still deferred to Lenin, and I loved him for that even more.

The school’s first bell disrupted my trance. I’d forgotten where I was meant to be.

“Good-bye, Stalina,” Stalin spoke from the poster. “Go to your classes; I’ll wait here for you. Go now—study hard and be a good young Communist.”

I sat down at my desk, still in a state of shock, looking around at my classmates to see if they noticed how I’d changed. No one could know the fire in my heart. Olga was busy fixing the ribbon in Amalia’s hair, and Yuri, the class comedian, was performing his version of Swan Lake when our teacher, Mrs. Tolga, scolded him mid pirouette and sent him to sit in the back even though we all could see he made her laugh along with the rest of us.

The class settled, and all was quiet except for the crack of our opening notebooks. The lesson on the board in bold block letters read: WRITE A POEM ABOUT HOW COMMUNISM HELPS ONE AND ALL.

I could only keep thinking, “Stalin spoke to me—he spoke to me.”

“Take me, I’m yours,” I whispered and scribbled over and over in my notebook. On another page I drew a copy of the poster, this time including myself at Stalin’s side, our collective gaze seeing past the streets and buildings of Leningrad to the fields and factories soon to be nourished with our country’s newfound power and wealth. My love was so new, and myself and my country so terribly naïve.

* * *

Stalina

Stalina